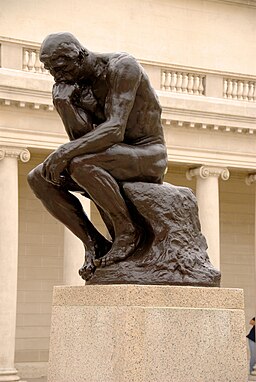

If to think and be aware of those thoughts (to think about thinking) is a defining feature of what it means to be human, why is it such a challenge to think about types of thinking? An answer to that question might help explain why design thinking is so difficult to translate into action and scholarship and why it continues to be the recipient of intense criticism and boosterism.

The other day a colleague reminded me of an essay on the demise of design thinking that I commented on in an earlier post. The post by William Storage adds further to the growing list of critiques of design thinking and ends this way:

In short, Design Thinking is hopelessly contaminated. There’s too much sleaze in the field. Let’s bury it and get back to basics like good design. Everyone already knows that solution-focus is as essential as problem-focus. Stop arguing the point. If good design doesn’t convince the world that design should be fully integrated into business and society, another over-caffeinated Design Thinking book isn’t likely to do so either.

Storage is right to argue that another book will not convince people of the merits of design or design thinking (which is different), but I can’t imagine it is just because of its merits. There appears to be something that troubles people with picking up metacognitive concepts.

Thinking about (Design) Thinking

Metacogntion is thinking about thinking and concepts like design thinking and systems thinking are, at their most basic, about the thought processes involved in contemplating systems or design. What commentators like Storage and Bruce Nussbaum are railing against is how this more sophisticated concept of design thinking (design metacognition if you will) has over time become synonymous at best, but a wholesale replacement at worst with a set of tools and creativity exercises.

Here we see the gap between the methods and their methodology.

Systems thinking, having had a few decades jump on design thinking seems to be faring better in that its common use is treated more as a metacognitive exercise than just a method, but only slightly. Why does adding thinking to something make it so difficult to communicate?

There is a reductionist push towards making thinking — design thinking, systems thinking, critical thinking, visual thinking — into a discussion of methods and tools. The concern, not unfounded, is that concepts like design thinking are pitched as a set of very simple techniques to provoke innovation while being stripped of its genuine innovation potential and reflective capacity, ironically removing the “thinking” part of the approach. These tools are manifest expressions of thinking and facilitators of it, but they are not thinking on its own.

The business and evidence of thinking

Maybe this is our fault for not putting ‘thinking’ into the development of these concepts from the start. For example, the field of design suffers greatly from a lack of scholarship and theory around its methods and approaches. Designers are a practical bunch and seek to create and build things over theorizing and submitting their own processes to research. There are notable exceptions to this of course, but overall it is safe to say given design’s pervasiveness in our world that we know relatively little about it.

Systems thinking (as it applies to human systems) is in a different position, almost an opposite position. Whereas design thinking has come from a long history of practice with little formal research supporting it, systems thinking has emerged largely from academia and has far less empirical support for its applications to social affairs.

Another issue is economic. The drive for innovation-led market advantages in many fields is pushing anything to support such activity — something design thinking can do — into high demand. Markets abhor vacuums so they get filled and early markets favour the swift and bold, not necessarily quality. As my doctoral advisor once told me when I was hesitating on publishing my research: “people remember the first, not necessarily the best“.

Thus, we have entire business enterprises founded on teaching people design thinking without much depth in the processes they use or intellectual foundations to support their work. They are out there in spades and contributing to the reasoned distrust, frustration, and dislike of design thinking by many who could be its biggest advocates. Whether that’s hopeless or not remains to be seen.

Where to?

So what is to be done? One option, that taken by Bruce Nussbaum, is to consider design thinking a failed experiment and seek alternative terms and concepts that capture the essence of what it does to improve innovative thinking, but in a manner that is less distorted. The challenge here is that, even if a new term does supplant design thinking, what is to prevent that concept from being co-opted and distorted as well with the same innovation-related market drivers in place?

Some argue that by formalizing design thinking into accredited programs, designations, certificates or degrees can assure quality just as we’ve started to see creep into the field of evaluation,. This presumes that have an empirically supported or widely agreed definition of what design thinking is and what are its core competencies. It also presumes we have the faculty with these skills and in positions to train people using methods tested to produce specific outcomes. Neither of these is true at present. This is the equivalent of suggesting that artists must have art degrees. Some artists do, but many do not and there is little to distinguish the difference in the quality of the work between them.

A third option, the more complicated one and the most flexible, is to consciously build a community of practice around design thinking aimed at improving the scholarship, research and communications about design thinking to enable the wider world to learn about it, debate it, and apply it. This is already starting to form through such venues as the Design Thinking LinkedIn group and the Design Thinking Network. To that end, we could see a tremendous opportunity for professional organizations such as DMI and AIGA to contribute to this by opening themselves up to the wider community in the focus of their events and training options. By increasing commitment from those doing design and design thinking to education and contemplative inquiry into their craft, we are naturally developing a field of practice that forms an attractor basin for better thinking and action.

Some further suggestions to support this point:

- Follow what psychology did after the American Psychological Association President George Miller suggested they “give away psychology” to the world. Psychology was once an elitist, opaque field of therapy and science and now is widely taught, incorporated into nearly every human-centred discipline, and is founded on a strong scientific and practice base. Democratize design thinking.

- Enlist creative professionals from fields like environmental studies, public health, social work, and education into the design thinking fold beyond traditional design disciplines. Get those living the spirit of Herb Simon who are trying to actively change current conditions into preferred ones — the social innovators, the public servants, the entrepreneurs of every stripe — to contribute their stories and insights on design thinking and get those into the public sphere for debate and dialogue.

- Fund and support more research programs beyond examples of my own modestly-supported Design Foundations project, which has sought to study design thinking by interviewing those experts that do it and the literature on its practice across disciplines. And rather than proclaim design thinking’s success and power, prove it and document it.

- Evaluate the programs that teach it, the processes used and determine what works, under what context, and document what happened along the way so we can learn more and be better at advocating for the power of design than simply proclaiming its worth.

Let’s contemplate more, study more, and reflect more about design thinking and maybe we’ll become better design thinkers.

What are your thoughts? Comment below.

Comments are closed.